NEB ambition

The ultimate ambition of the New European Bauhaus is to achieve transformation. To do this, the NEB Compass has identified specific levels of ambition that outline the desired outcomes for each of the NEB values.

The ultimate ambition of the New European Bauhaus is to achieve transformation. To do this, the NEB Compass has identified specific levels of ambition that outline the desired outcomes for each of the NEB values.

These areas refer to the five key domains of intervention that CrAFt's New European Bauhaus Impact Model considers essential for guiding and evaluating complex urban initiatives.

The participation level refers to the degree or extent to which individuals or groups are actively involved or engaged in a particular activity, project, or process. It assesses the depth of their involvement, contributions, and commitment, ranging from minimal or passive participation to active and dedicated participation.

The New European Bauhaus (NEB) aims to promote the values of sustainability, aesthetics, and inclusion in the design and transformation of urban spaces. It emphasises the integration of environmental, social, and economic considerations to create harmonious and innovative living environments.

According to the Smart City Guidance Package, there are seven stages to plan and implement smart city projects. These stages propose a logical and coherent roadmap for city initiatives involving many stakeholders.

Over a decade ago, a group of visionary residents embarked on a mission to create Europe’s most sustainable floating community. What began as a dream to transform an industrial landscape in Amsterdam into a vibrant, eco-conscious neighbourhood has blossomed into a thriving reality. With strong determination and collaborative spirit, the residents of Schoonschip have turned their vision into a blueprint for sustainable living.

Situated in the post-industrial area of Buiksloterham, Schoonschip represents a transformational journey from pollution to regeneration. Once dominated by factories and warehouses, this waterfront area has been reimagined as a sustainable residential oasis. With its innovative approach to urban renewal, Schoonschip serves as a beacon of hope for communities seeking to revitalise neglected landscapes.

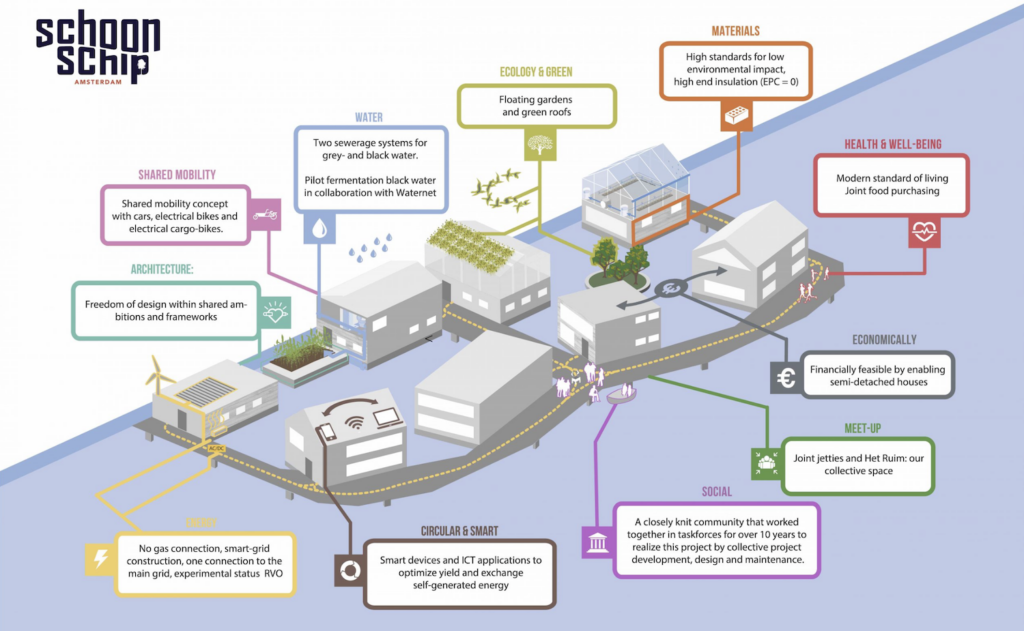

At the core of Schoonschip’s ethos lies a commitment to ecological and social sustainability. With 144 residents living in 30 arks—46 households, as some of the arks contain two households—and sharing a common goal, every aspect of community life is infused with a sense of environmental stewardship. From designing energy-efficient homes to cultivating shared green spaces, sustainability is woven into the fabric of daily life.

The numbers speak volumes: 516 solar panels harness the power of the sun, 30 heat pumps provide renewable heating solutions, and 60 thermal panels contribute to energy efficiency. Schoonschip is not just a neighbourhood—it’s a living laboratory for sustainable technologies.

By embracing cutting-edge infrastructure and renewable energy sources, residents have created a model for environmentally responsible living.

The success of Schoonschip is proof of the power of collaboration and community engagement. For over ten years, residents have worked tirelessly to design, develop, and realise their vision of sustainable living.

Through shared decision-making and collective action, they have overcome challenges and embraced opportunities, forging bonds that transcend mere neighbours to become a close-knit community.

The Schoonschip community actively shares resources to promote sustainability and strengthen social bonds.

They collectively share electricity generated from solar panels, utilising interconnected batteries to distribute and sell surplus power. Through a sharing mobility platform called Hely, members share cars, electric bicycles, and cargo bikes, reducing individual reliance on personal vehicles.

Some food is sourced collectively from local farmers, currently focusing on vegetables and eggs, fostering a connection to local agriculture and reducing carbon emissions associated with food transportation. Additionally, the community utilises a WhatsApp group to share, borrow, and exchange various items, creating a culture of resourcefulness and mutual support among neighbours.

The objective of the Schoonschip project is to realise a unique vision of a sustainable community. While many of the project’s components, such as sustainable building practices and collective private commissioning, are not entirely novel on their own, the combination of these elements, along with several new ones, presents a process that has not been attempted before.

Schoonschip is, therefore, rooted in three main pillars:

Schoonschip’s governance model evolved from a simple idea in 2008 to a complex organisational structure involving 46 households striving to create a sustainable floating community. Initially conceived as a collective endeavour inspired by the “GeWoonboot” documentary, it transitioned into the Schoonschip Corporation by 2011 with the support of some architecture professionals, and eventually applied to build on the Johan van Hasselt Canal in 2013.

While the corporation managed shared aspects like the jetty and smart grid, the absence of an external project developer led to organisational complexities. At that point, the project shifted from collective to private commissioning, allowing each household to hire its own architect and contractor. In spite of it, Schoonschip’s board needed help balancing individual preferences with collective and environmental demands, leading to numerous challenges and extensive coordination efforts.

The decision to organise without a project developer imposed significant burdens on the board members, prolonging the project’s duration and compromising sustainability goals. Despite the challenges, the project’s unique character and community-driven ethos were preserved.

Reflecting on the journey, the Schoonschip community acknowledges that a more centralised approach might have expedited the process and enhanced sustainability outcomes. However, this approach would have limited individual expression and resulted in a smaller community size.

Nowadays, the organisation consists of two entities, a owners association for internal affairs, and the Pioneer Vessel for external affairs like tours, presentations, and participation in various European, national and local research projects.

The Pioneer Vessel is a foundation established in 2019 and run by the residents to coordinate various activities and promote sustainability on behalf of the Schoonschip community. It serves as a “living lab” for sustainable innovations and experiments. It brings together 105 pioneers, consisting of Schoonschip residents, to coordinate various activities to promote sustainability within the community.

Some of the lessons learned from the development of Schoonschip underscore the challenges and complexities inherent to community projects and the need to balance between affordability and sustainability:

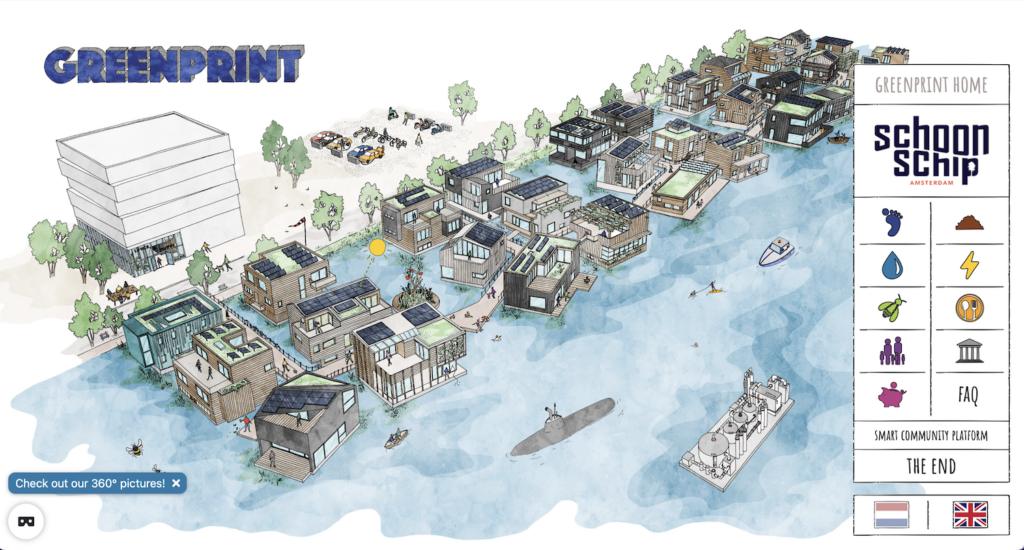

In closing, exploring the websites of the Schoonschip community offers a rewarding experience, unveiling a wealth of information about their governance and financial models, energy and water management systems, philosophical approach, and harmonious relationship with nature and food.

One can delve into the narratives of select residents, understanding their motivations for choosing this unique lifestyle and how they’ve customised their homes to align with their values.

You will even get a glimpse into Schoonschip’s technological approach to sustainable living by exploring their Smart Community Platform (SCP), the hub of their smart-grid network.

Written by Jose Rodriguez

Revised by Julia Emmering, Schoonschip resident

Photos by Isabel Nabuurs

Illustration by Metabolic